There was a time when retirees could visit the Social Security Administration website and use a break-even calculator to estimate how long it would take for higher monthly benefits from delayed claiming to make up for the checks they gave up by claiming early.

That tool is gone.

The agency removed it in 2008 after concluding that many users misunderstood what the calculation actually showed. Too often, people assumed they would die before reaching the break-even age, effectively treating the analysis as a bet against their own longevity.

The shift away from break-even analysis was part of a broader effort to improve financial literacy around what is arguably the most consequential retirement decision many Americans make: when to claim Social Security.

Jason Fichtner, who was acting deputy commissioner at the time, said the agency recognized the limits of promoting an overly simplified break-even framework.

“While a break-even analysis can show when delayed benefits might catch up,” Fichtner said, “the SSA now emphasizes that waiting provides inflation-adjusted income for the rest of your life and protection against outliving savings, a key insurance function, especially important for longer-lived spouses.”

Moving away from break-even math, he said, encourages a broader analysis that incorporates cost-of-living adjustments, survivor benefits, taxes, other income sources and longevity risk.

Why many financial planners say focusing on “breaking even” can lead retirees to make the wrong Social Security claiming decision – and what to consider instead.

Why many financial planners say focusing on “breaking even” can lead retirees to make the wrong Social Security claiming decision – and what to consider instead.

Photo by andresr on Getty Images

The math that leads people astray

I’m not a fan of people using the break-even analysis mostly because people don’t undertand how life expectancy is rising in the U.S. and because people don’t understand the probabilities of living beyond life expectancy. But I haven’t given the topic much thought until this week.

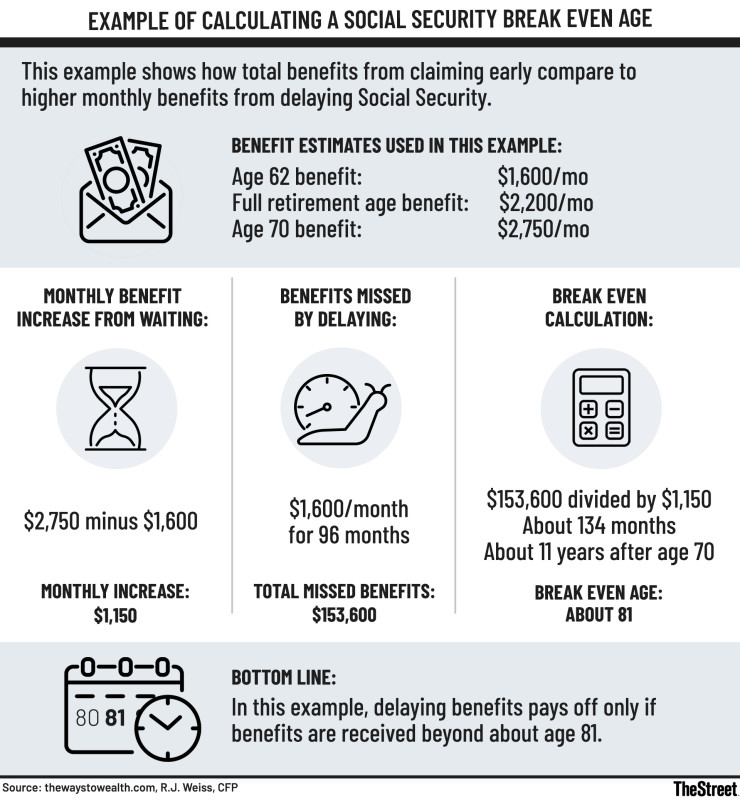

It resurfaced in my life after a financial planner shared a graphic on Facebook comparing lifetime benefits from claiming early with the higher monthly checks that come from delaying Social Security.

In the example, delaying benefits “paid off” only if the individual lived beyond roughly age 81.

thewaystowealth.com, R.J. Weiss, CFP

And that conclusion is precisely why many advisers say break-even math points retirees in the wrong direction.

Related: Here’s when you should claim Social Security

Once someone reaches age 62, the odds of living into their 80s are substantial. A 62-year-old man can expect to live about 20 more years, to roughly age 82. A 62-year-old woman can expect to live about 23 more years, to roughly age 85.

Seen that way, break-even analysis implicitly asks people to bet they will fall on the wrong side of life expectancy.

A better frame, advisers say, is risk management, not arithmetic.

A starting point, not a decision rule

Most financial planners say they use break-even calculations only to frame the conversation, not to determine the recommendation. At best, the math illustrates the trade-off between smaller checks claimed earlier and larger checks received later. At worst, it crowds out more important planning considerations.

Melissa Caro, a certified financial planner with My Retirement Network, said break-even analysis works as a context-setter, not a verdict.

“When advisers lead with break-even ages, clients often internalize the wrong takeaway,” Caro said. “They start thinking in terms of winning or losing based on how long they live.”

That framing, she said, fuels fear and regret rather than clarity and downplays Social Security’s role as a baseline income that supports the rest of the retirement plan.

Crystal Cox, a certified financial planner with Wealthspire Advisors, said she also treats break-even as just one data point.

“It helps explain the math,” Cox said, “but it has to be placed in the broader context of health, family longevity, risk tolerance, taxes and cash flow.”

When early claiming can make sense

Advisers cautioned, however, that rejecting break-even analysis does not mean delaying benefits is always the right answer. For some retirees, especially those with limited savings or uneven income early in retirement, claiming earlier can be a practical necessity rather than a mistake.

Several planners said early claiming may be appropriate when delaying benefits would force unsustainably high portfolio withdrawals, reduce financial flexibility, or compromise a retiree’s ability to meet near-term spending needs. In those cases, cash-flow stability may outweigh the long-term value of a higher monthly benefit.

Social Security is not an investment

Across responses, advisers consistently said the core flaw in break-even analysis is that it treats Social Security like a return-seeking investment rather than what it actually is: longevity insurance.

David Haas, a certified financial planner with Cereus Financial Advisors, said he rarely relies on break-even analysis.

“The risk is not dying early and not getting your money back,” Haas said. “The risk is living too long and running out of money.”

Because benefits are indexed for inflation, he said, Social Security functions as one of the most effective forms of longevity insurance available. Delaying benefits raises the base on which future cost-of-living adjustments are calculated.

“Annuities and pensions are typically fixed,” Haas said. “Social Security is not.”

For households without pensions or rental income, advisers noted, Social Security may be the only reliable source of lifetime, inflation-adjusted income they will ever have.

Opportunity cost and relative returns

Some advisers also view delayed claiming through a relative-return lens.

David Demming, a certified financial planner with Demming Financial Services Corp., said that for clients in good health with stable cash flow, he generally leans toward waiting until age 70.

He compares delayed retirement credits to bond yields, noting that benefits increase by about 8% a year after full retirement age, a rate he said compares favorably with recent 10-year Treasury yields.

Longevity risk outweighs dying “too soon”

Many advisers said retirees fixate on the possibility of claiming later and dying early, even though the more consequential risk is the opposite: living longer than expected with inadequate income.

Advisers stress this does not mean early claiming is always wrong, but that the downside of reduced lifetime income grows larger the longer someone lives.

“If you base your decision on a break-even analysis, you are in effect betting that you are going to die earlier,” said Artie Green, a certified financial planner with Cognizant Wealth Advisors.

“Unless you have a health condition that materially shortens life expectancy, why would you choose that bet?” he said.

Related: The $83,250 secret every solo entrepreneur needs to know for 2026

Dan Galli, a certified financial planner with Daniel J. Galli & Associates, said health is one of the few factors that can justify prioritizing earlier claiming.

Clients with serious or well-documented health concerns may be better served by claiming earlier, he said, while healthier clients need to plan for the risk of living longer than expected.

Survivor protection gets ignored

For married couples, advisers said one of the biggest shortcomings of break-even analysis is what it leaves out: the impact of claiming decisions on the surviving spouse.

Joon Um, a certified financial planner with Secure Tax & Accounting, said break-even analysis assumes a fixed lifespan and ignores survivor protection.

“The decision isn’t about beating a break-even age,” Um said. “It’s about protecting the surviving spouse with a higher guaranteed benefit.”

Jeremy Keil, a certified financial planner with Keil Financial Partners, said break-even math also fails to distinguish between the lower and higher benefit, even though the higher benefit is the one that continues for the survivor.

Taxes and coordination matter

Break-even analysis also ignores taxes and income coordination.

Ryan Marshall, a certified financial planner with Cetera Advisor Networks, said break-even can help start the right conversation, but only if it does not become the conclusion.

“Up to 85% of Social Security can be taxable,” Marshall said. “Claiming decisions have to be coordinated with IRA withdrawals, Roth conversions and Medicare premiums.”

Expected utility, not expected value

Several advisers said the deeper problem with break-even analysis is that it focuses on expected value, or which option pays more on average, rather than expected utility, or which option best protects against the outcomes retirees fear most, such as outliving their income.

That distinction helps explain why break-even math can be technically correct and still lead to poor decisions.

When break-even can help

Used carefully, advisers said, break-even analysis can still play a role.

Leah Granger, a certified financial planner with Thorley Wealth Management, said it can help narrow options when comparing full claiming strategies.

“It’s an interesting data point,” she said, “but it doesn’t capture the broader impact on household income over time.”

Joseph Piszczor, a certified financial planner with Washington Family Wealth, summed it up this way: break-even analysis is easy to understand and helpful for framing the conversation, but it should be integrated into a broader financial plan, not used as a stand-alone recommendation.

Longevity risk is a key consideration

Ultimately, advisers said, the Social Security claiming decision is about managing longevity risk, not optimizing a spreadsheet.

“Break-even analysis misses the central issue,” Haas said. “Because it’s indexed for inflation, Social Security works as longevity insurance. You want those cost-of-living increases calculated on the highest base possible.”

That, advisers said, is why breaking even is the wrong goal.

Related: The Impact of Recent Social Security Changes on the Program’s Solvency