Dave Ramsey is an immensely popular personal finance pundit, especially among audience members who share his traditional family values approach to money and enjoy the evangelical bent he incorporates into his saving and spending advice. Some might even call him a personal finance preacher.

Best known for The Ramsey Show, his eponymous daily video and radio broadcast, and his 10+ books, Ramsey’s financial advice reaches an estimated tens of millions each week. Total Money Makeover, a WSJ and NYT bestselling book first released in 2003, is by far Ramsey’s most popular, and it lays the foundation for much of the advice he’s espoused since its initial release.

With over 8 million followers on Facebook, 6 million on Instagram, 3 million on TikTok, and 1 million on X, it’s clear that a huge number of Americans look to Ramsey for practical advice on things like making money, getting out of debt, and saving for a home. Nevertheless, his somewhat unique approach to certain aspects of personal finance has drawn a fair amount of criticism, and in some cases, simple math contradicts certain elements of his advice.

Here, we explore three of Dave Ramsey’s most controversial personal finance tips and why they probably aren’t right for everyone (but might work well for some).

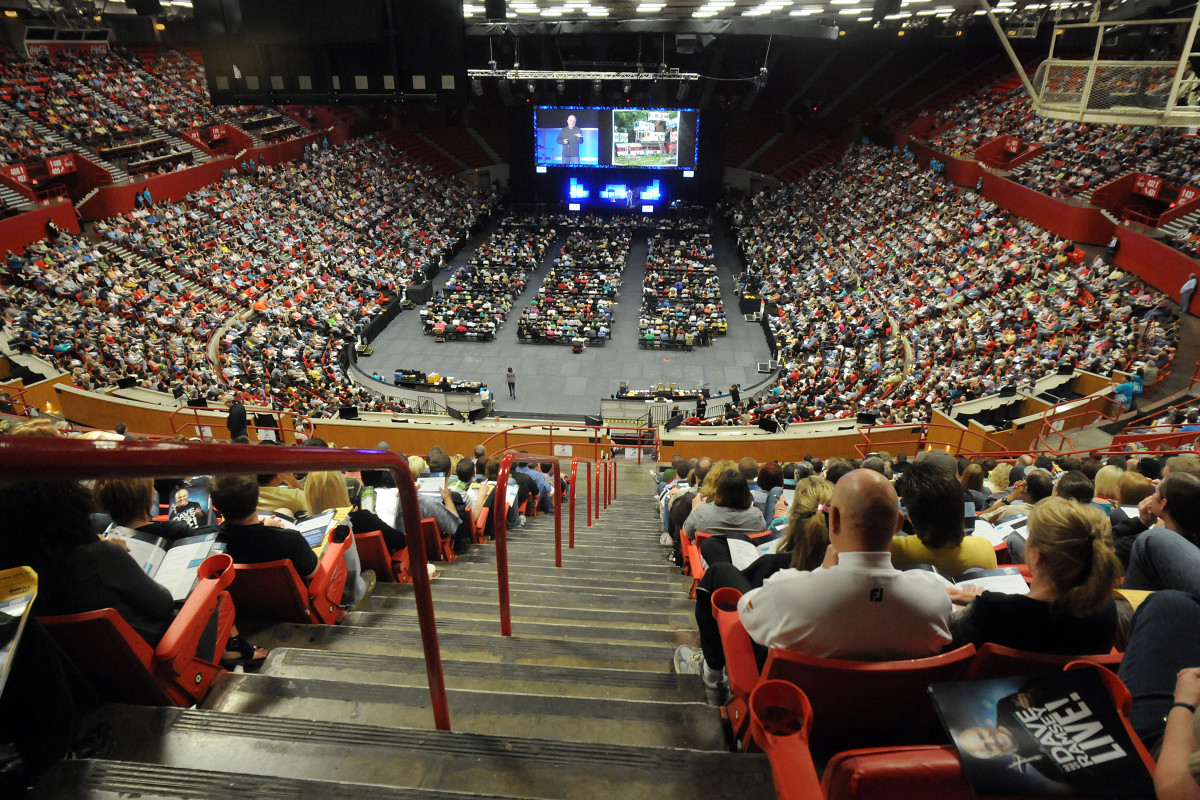

Despite Ramsey’s massive popularity, his financial advice is aimed at a very specific subset of the public.

Despite Ramsey’s massive popularity, his financial advice is aimed at a very specific subset of the public.

Photo by Jackson Laizure on Getty Images

1. Pay off smaller debts first

Getting out of debt is a core tenet of Ramsey’s Baby Steps, the backbone of his popular methodology for achieving financial freedom. In fact, it’s the second of seven steps, preceded only by saving $1,000 for an emergency fund.When it comes to paying off debts, Ramsey recommends the snowball method, which refers to paying the minimum monthly payment on each of your debts while using any extra money to pay down your smallest debt. Once the smallest debt is paid off, the snowball method teaches, move on to the next-smallest, and so on.

According to Ramsey’s website, the debt snowball method “creates behavior change through motivation and consistency, helping you stay focused as you eliminate debt.” In other words, its efficacy comes from the psychological boost that accompanies paying a debt off in full, which can then help build consistent, positive habits when it comes to debt management in general.

The debt snowball method, though, fails to address the fairly dangerous elephant in the room—interest. Compounding interest, which Albert Einstein referred to as the “eighth wonder of the world,” can turn a manageable amount of debt into an insurmountable mountain of debt fast. Imagine Sysiphus rolling his boulder up the hill, but each day, the hill grows taller—that’s what can happen when high-interest debt isn’t prioritized.

Related: Dave Ramsey’s net worth: The retirement expert’s wealth in 2025

Mathematically speaking, paying off high-interest debt first (after making the minimum required payments on all debts to avoid default) is the cheapest way to get out of debt because it targets your fastest-growing debt first, so that you can get out of debt faster while spending less overall to do so.

This strategy, essentially the opposite of the snowball method, is called the avalanche method. Suze Orman, a peer of Ramsey’s in the personal finance media landscape, recommends using this strategy to eliminate credit card debt (although she calls it the roll-down method).

Related: Suze Orman’s 5 best pieces of financial advice

When does the debt snowball method make sense?

The debt-snowball method isn’t totally without merit, and Dave Ramsey is far from the only finance expert to recommend it. Which method actually makes more sense for an individual, though, depends on whether the hurdles preventing them from becoming debt-free are purely financial, or if there is a psychological or behavioral element as well.

In the latter case, the debt snowball method may, in fact, be more effective. Studies from both Northwestern Kellogg and the Harvard Business Review have indicated that the snowball method may actually lead to faster total debt repayment in many cases.

2. Avoid credit cards at all costs

Quite famously, Dave Ramsey advises his listeners (and readers) to cut up their credit cards and swear off high-interest plastic for good. According to his website, “There’s no beating the system when it comes to credit cards. Even if you think you can make it work, it’s just not worth the risk. Period.”

That statement is patently false. I know this because using credit cards responsibly is one of the best things I’ve done for my own financial well-being. In fact, the highly competitive modern credit card ecosystem presents the perfect opportunity for young, working-class folks to earn some free money while building their credit scores—assuming they can keep their spending in check.

Related: Scott Galloway’s 5 best wealth-building tips for young people

I got my first credit card shortly after turning 18, around the same time I put myself in debt to the tune of around $35,000 to attend college. With no credit history, there weren’t many credit cards I qualified for, so my first one was pretty basic. It had a high APR (interest rate), a low credit limit, and little to offer in the way of cash back rewards.

I put every purchase I made on this card and paid off the full balance each month directly from my checking account, making sure to never spend more than I would if I were paying with cash or a debit card. After a year or so, my credit score had gone up enough that I qualified for some better credit cards—the type with signing bonuses and cash back rewards.

When I got new credit cards, I left my old ones open rather than closing them, as the longer my credit history (i.e., the age of my oldest credit account) and lower my credit utilization rate (current credit card debt divided total credit limit across all cards) both increased my credit score, allowing me to qualify for more and better credit cards.

Because the credit card market is so crowded and competitive, many cards offer a cash bonus to new applicants if they are approved and spend a minimum amount within the first three or six months of account opening. By putting all of my purchases on my newest card, it was usually possible for me to meet these minimum spend requirements and earn $50, $100, or $200 in free money every three to six months before applying for a new card and chasing another signing bonus.

After college, I lived for a time in an apartment complex that allowed rent payments to be made by credit card—this made it incredibly easy to spend the minimum amounts necessary to earn sign-up bonuses on new cards. As my credit improved, I was also able to qualify for more specific cards that earn high rates of cash back on the things I spent the most on—namely, groceries, gas, and dining.

As an added bonus, my improving credit history and credit utilization rate helped gradually offset the negative impact of my student loan debt on my credit score.

The takeaway? So long as a credit card doesn’t have an annual fee and you pay your balance in full each month, any signing bonuses and rewards it offers are free money, and if you’re using a debit card or cash, you’re leaving that money on the table. Responsible credit card use also does wonders for the credit score.

To this day, I carry at least three credit cards at all times—one that earns 4% cash back on dining, one that earns 5% cash back on groceries, and one that earns 5% cash back on gas.

Here’s what a Reddit user had to say about Ramsey’s credit card advice:

Comment by from discussion inCreditCards

View the original article to see embedded media.

When ditching credit cards is actually good advice

Despite all of their potential benefits, credit cards do have a dark side. Ramsey is correct in calling them dangerous, and they may not be the best tool for everyone.

When using credit cards to build credit and earn rewards, it’s imperative to remain vigilant, checking your credit card and banking accounts frequently to ensure you’re not spending money you don’t have.

More on personal finance:

- Dave Ramsey’s real estate advice: 5 tips every first-time homebuyer should follow

- Barbara Corcoran’s 4 best personal finance insights

- Mark Cuban’s 5 best financial insights every investor should know

Folks who are prone to impulsive purchases and casual overspending may do better to follow Ramsey’s advice and avoid credit cards for the most part—after all, they’re designed to put people in debt. Credit cards are only profitable for banks because the amount of interest paid by cardholders who carry a balance far outweighs the amount of money the banks pay out to responsible cardholders in bonuses and rewards.

And with credit card interest rates averaging around 24% as of late 2025, carrying one or more credit card balances (i.e., making minimum payments rather than paying your balance in full each month) is a surefire way to land you in the shadow of a rapidly growing pile of debt.

3. Pay off all debt before investing

Another one of Ramsey’s questionable admonishments is to refrain from investing until you’ve paid off all of your non-mortgage debt (e.g., student loans, auto loans, credit cards, etc.). The logic of this advice is fairly sound, in that paying down debt is an investment with a guaranteed rate of return. When you pay off a debt with a 10% annual interest rate, you’re essentially earning 10%. Investing, on the other hand, usually involves the stock market, which is volatile and does not guarantee a positive return, at least on an annual basis.

That being said, most average people invest via a retirement account like an employer-sponsored 401(k). These accounts tend to offer pre-diversified investments, such as total market ETFs or mutual funds that aim to produce modest but consistent positive returns over the long term.

Many of them offer employer matching up to a certain percentage of each paycheck. For instance, a 401(k) with 3% matching allows an employee to divert up to 3% of each paycheck into a tax-advantaged investment account, with the employer contributing the same amount, essentially upping the employee’s retirement contribution to 6% of their paycheck. It’s like a buy-one-get-one-free deal for the stock market. In other words, not contributing up to the employer match percentage is equivalent to turning down free money.

Additionally, since 401(k)s are long-term retirement accounts, employees don’t typically withdraw from them until retirement, meaning that their money remains invested for decades. And over decades, the stock market virtually always goes up—significantly. Between employee and employer contributions, reinvested dividends, and the massive capital gains that usually result from the market going up over the course of three or more decades, the risk of delaying investment usually outweighs the risk of contributing slightly less to debt payments.

It’s important to note, however, that without employer matching, this scenario becomes much blurrier.

Related: Robert Herjavec’s financial wisdom: The ‘Shark Tank’ star’s 4 takeaways for investors

When waiting to invest is actually good advice

Mark Cuban, another wealthy finance expert, tends to agree with Ramsey. He has said that paying off debt is the best investment you can make, as the interest you avoid paying by doing so likely outweighs the returns you’ll get in the market. This is typically true in the short term, so debt payments should always take precedence over stock trading or other shorter-term investments.

Additionally, for those living paycheck-to-paycheck with little to no disposable income, debt repayment should always be a top financial priority, especially if no employer-sponsored, tax-advantaged investment account is available.

High-interest debt, such as credit card debt, also has the potential to outpace the gains someone might achieve even through an investment account with employer matching, so there is certainly an argument to be made for pausing 401(k) contributions temporarily while wiping those balances out.

The same can’t necessarily be said for lower-interest debt, such as student loans. For someone with a decent buffer of disposable income, contributing to an employer-matched investment account while also paying down debt (ideally using the avalanche method) is often a good way to balance responsibility with opportunity cost.

Related: 3 things Mark Cuban & Dave Ramsey agree on about personal finance

The takeaway

The main issues with Ramsey’s advice stem from his psychologically focused approach to personal finance, and for that reason, he’s not necessarily wrong to advise avoiding credit cards and paying down one’s smallest debts first—this approach definitely resonates with some audience members.

Some of his listeners, acknowledging that his advice isn’t for everyone, have called his show “AA for the money” and remarked that “His goal is to help people who have low financial literacy and are already in a bad spot with debt.”

Ramsey’s tips seem to assume that his listeners lack discipline, so his solutions are often built around the psychology of someone who can’t be trusted to avoid spending what they don’t have. The snowball method of debt repayment, similarly, is geared toward someone who needs the reward of paying off a small debt in full before they can believe in themself enough to tackle the rest of their debt.

At the end of the day, Ramsey’s risk-averse, discipline-focused baby steps approach may be the most effective formula for those who are deep in debt and need a simple, rules-based roadmap toward financial freedom.

For those who want to use the financial system as efficiently as possible, though, there are better ways to get out of debt and build wealth.