AI enthusiasts had been hopped up on the hopium that creator OpenAI would achieve a major breakthrough with GPT-5, the latest installment of the software behind ChatGPT.

But if the social media reception thus far is any indication, it appears more that GPT-5 is breaking brains, rather than expectations. That’s because, by most accounts, the GPT-5 hype train has derailed; expectations were far too great and the results are too few.

For years, CEO Sam Altman and his crack team of AI engineers hyped up GPT-5 as if it would be a fantastic leap in the grand scheme of AI models. Its coming was augured as borderline biblical among the San Fran-centric tech elite.

In highly-online circles, AI accelerationists joked that there were just “two years left” to make money and “escape the permanent underclass” before OpenAI’s long-awaited model launched and took all our jobs.

Since GPT-5 launched, the tone has shifted. Many of those same boosters are backtracking, seemingly a little less sure about the timeline to artificial general intelligence (AGI), the kind of AI that can take on human tasks and learn without much intervention.

That’s not to say that the model isn’t a form of progress, but to many, the new GPT-5 model is seen as a downgrade. That’s got to be a disappointment, but there’s arguably somebody who lost even bigger than OpenAI in all of this.

We’ll give you a hint: he just spent billions to hire many of the forefathers of the now-criticized model.

Mark, We Feel You

In June, Meta (META) CEO Mark Zuckerberg went on a hiring spree, spending $14.3 billion to buy a 49% stake in Scale AI, a data labeling and model evaluation software.

Really, it wasn’t Scale AI that Zucc really wanted. It was CEO Alexandr Wang, who now leads the company’s ‘Superintelligence’ division. That big buy preceded a series of big buys by Meta’s top dog, who was soon on the prowl for top AI talent.

Blank checks in tow, Zuckerberg raided the cabinets of competitors like OpenAI, Anthropic, and smaller AI labs like Thinking Machine Labs. He reportedly offered one researcher at the latter up to $1.5 billion in compensation in exchange for six years of work.

However, many hires came from OpenAI. Their departure signaled, at least to the AI-enthused, that AGI or a more omniscient super intelligence (ASI) was likely still years away. But as fate would have it, many of those poached away by Meta were almost certainly involved in GPT-5. Based on what they were seeing, surely they knew as much.

And so the researchers took the money, joined Meta, and OpenAI released its most underwhelming model in as many years. You’d have to think that Mark isn’t too happy about that. Maybe the singular silver lining is that it sets the bar low for whatever Meta is working on right now.

But aside from the massive spending on talent, Meta’s AI aspirations are running into another wall: their cash and cash equivalents.

Reality Labs 2.0?

During the pandemic, Zuckerberg went all-in on the metaverse, positioning Meta for an AR and VR-driven future. It was so sold on the opportunity, it even changed its corporate name to Meta, reflecting its embrace of the technology.

The Reality Labs division of the company — which encompassed everything from its Oculus VR headset, its new Ray-Ban AR glasses, and the lesser-known Horizon Worlds online platform — has cost Meta over $50 billion since its rebrand in Aug. 2020.

A few years later, it’s hard not to compare Meta’s newfound embrace of AI to Reality Labs. It’s similarly costly and the company is all-in. It might be less cavalier about the business opportunity here, because if AI does eventually work out, companies attached to the tech might make a lot of money.

But for the moment, it’s hard to ignore that ‘AI technology’ (large language models, for the most part) lose gobs of money. That goes for OpenAI, Anthropic, and also Meta.

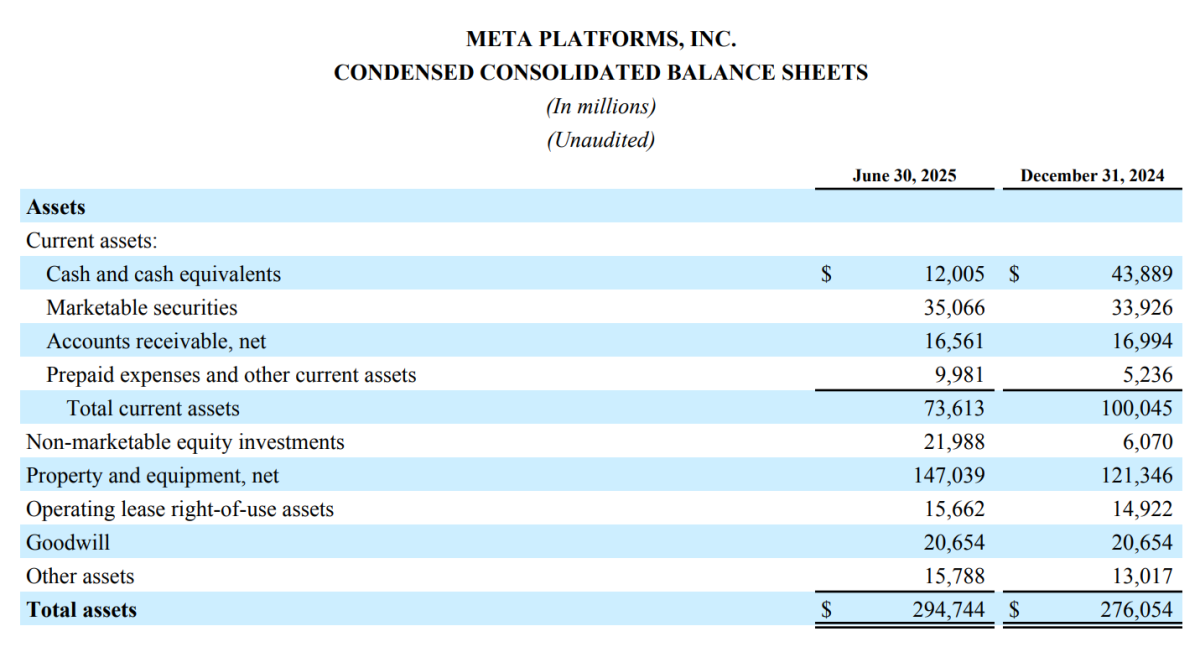

It’s a lesser-discussed component of its earnings, which were lauded by investors. But check out the balance sheet and you’ll see the cash has almost gone. Six months ago, the company had $43.8 billion in cash and cash equivalents. Come Jun. 30, they had $12 billion.

Meta’s condensed consolidated balance sheets, Q2 2025

Meta’s condensed consolidated balance sheets, Q2 2025

Most of that has migrated to the Property and equipment section, implying that this cash is being invested in buildout. But there’s reason to worry about overbuild, at least if you take Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella at his word.

Still, as if burning through $31.8 billion in cash and cash equivalents in the last six months wasn’t already cause for hysterics, the company is looking for more dry powder. It recently struck a $29 billion private credit deal, seeking to continue scaling.

Could Meta really crack the code?

Of course, all this spending likely means little if Meta makes it to artificial general intelligence (AGI) first. Though, there’s still some conjecture if that’s possible with the current angle of attack employed by leading AI labs (that is, training large language models).

Even if investors are onboard with the potentially years-long commitment of capital and time, you’d have to imagine they’d want to start to see evidence of scale from the technology. At the least, some sort of indication that this is going to start paying off long before the AI can do everything that its boosters swear by it to.

Maybe in this market, with valuations at record highs, there is increased tolerance for the timeline. There is hopium aplenty right now. But as AI agents struggle to breakthrough in enterprise settings and leading AI models remain wildly unprofitable, you’d have to expect that the seemingly infinite amounts of money being thrown into AI will eventually have to pale some sort of payoff.

That would mean more expensive credits and less access to the technology, unless AI upstarts can find unlimited processing power and energy sources to bring the “cost of intelligence” down to zero. Right now, much of this is subsidized by the venture capital class. (And at Meta and Google, the cost is being subsidized by ad businesses, likely some indication of where the tech is inevitably going.)

If the payoff isn’t painfully obvious soon, maybe you start to see some investors revolt next year. After all, every dollar expended on capex is a dollar not spent on dividends and share buybacks.

That might be okay for now, but with Meta up 27% year-to-date, one has to wonder how long investors will actually have to wait for the future to finally arrive.